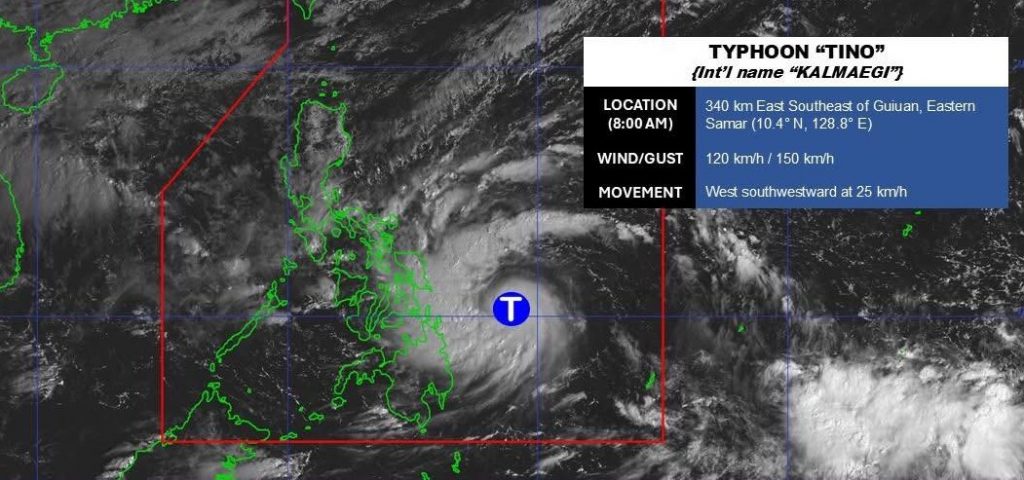

Satellite image of Tropical Cyclone Kalmaegi (2025)

Photo Source: DOST-PAGASA

What is science telling us about climate change?

In 2024, global temperatures were warmer by 1.55°C than the pre-industrial average[1]. This marks the first year in modern history that the 1.5°C warming limit has been exceeded. While it does not indicate that the Paris Agreement goal to “pursue efforts to limit the increase [of global temperatures] to 1.5°C” is out of reach, it means that the tipping point of the climate crisis is closer to becoming reality.

The findings of several scientific reports released within the past yearreveal the following:

- Concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide are higher by 51%, 165%, and 24%, respectively, than their pre-industrial levels[2];

- The past 10 years (2015-2024) mark the warmest decade in the past 175 years;

- Short-lived climate pollutants such as methane, black carbon, and hydrofluorocarbons, which are more potent global warming pollutants than CO2, contributed 30-40% of total GHG emissions in 2024[3];

- The average person in high-income countries produces GHG emissions more than 30 times higher than those in low-income countries. More than 80% of the global emissions come from high and upper-middle income nations[4].

The Asia-Pacific region’s contribution to CO₂ emissions continues to increase[5].

- Asia-Pacific accounts for approximately 60% of current global GHG emission; however, its average per-capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion is much lower than in developed countries.

- The largest share of these emissions come from coal-dependent energy systems, accounting for 52.2% of global energy-related CO2 emissions and 33% higher than in 2010.

- The region contributes 14% of global emissions attributed to the transport sector, driven by rapid industrialization and urbanization.

2024: a year of climate extremes

Many parts of the Asia-Pacific experienced record-setting extreme weather events in 2024, driven by unprecedented warming in a region marked with a temperature increase that is nearly double the global average. For the first half of the year, West, Central, South, and Southeast Asia were enveloped by a heat wave, attributed to factors including climate change and the fifth-strongest El Niño on record[6]. Among its impacts on countries are the following:

- The burning of fossil fuels caused the heatwave-induced warming in West Asia and the Philippines to be 1.7°C and 1.2°C higher, respectively. Human-induced climate change increased the probability of such an event by five times for West Asia, while the event would have been impossible in the Philippines without it[7].

- India experienced record-breaking temperatures between March and June, with 37 cities reporting temperatures of over 45°C and leading to 733 deaths due to heat stroke[8].

- Extreme temperatures in Bangladesh were as much as 16°C more than the yearly average, affecting the education of up to 33 million children by April[9].

- The heatwaves led to lower crop yields, water shortages, and heightened health risks for farmers in multiple countries across the continent, such as Bangladesh, Laos, and Pakistan. In the Mekong Delta, impacts of this extreme weather event on the agricultural sector include reduced freshwater flow, the resulting saltwater intrusion, and reduced rice yields[10].

Towards the end of the year, the region felt the brunt of extreme rainfall, flooding, and tropical cyclones, including during the conduct of UNFCCC COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. These events occurred in a short period of time that gave communities little to no time to recover or prepare for the next event, resulting in compounding and cascading climate risks and higher socioeconomic costs.

- In November, Thailand and Malaysia experienced six months’ worth of rainfall in five days due to the northeast monsoon. It led to 27 deaths, a combined 671,410 families affected, and health facilities and schools closed down[11].

- In late September, Nepal suffered from its heaviest rainfall recorded since at least 1970, causing at least 224 deaths, more than 13 thousand people being rescued, and bridges, highways, and hydropower stations damaged[12].

- In the third week of August 2024, heavy rainfall caused severe flooding in eastern Bangladesh, which killed 13 people and affected about five million people.

- A total of six tropical cyclones, including three Category 3-or-above typhoons, battered the Philippines in a span of four weeks between October and November. They collectively caused at least 171 deaths, 700 thousand people displaced, and thousands of hectares of farmland destroyed[13]. The occurrence of three such typhoons in a short period of time was made 25% more frequent due to fossil fuels[14].

Projected climate change

Without urgent and drastic interventions, billions of currently vulnerable people in the Asia-Pacific would be placed at an even higher climate risk, resulting in much higher social, environmental, and economic losses and damages[15]. The occurrences of extreme heatwaves are likely to increase across the region, leading to impacts including shrinking glaciers, fewer cold days and nights, and higher agricultural losses.

Aside from temperature extremes, many of the climate drivers in the region would be affected by how oceans are affected by emissions, as oceans absorb an estimated 90% of the excess heat that is trapped due to anthropogenic global warming.

- Sea levels would rise up to three times above the global average, reaching up to 0.8 m by 2100, placing coastal ecosystems, assets, and communities at risk under the SSP5-8.5 scenario or “business-as-usual”.

- Climate models show a reduced frequency of tropical cyclones but an increase in the proportion of category 4-5 tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific, likely leading to higher losses and damages to countries along the “typhoon belt”.

- Monsoonal rainfall would increase in East, Southeast, and South Asian lands, while monsoonal winds would become generally weaker with different magnitudes per region.

- Oceans would continue to become more acidic for the rest of the 21st century, threatening marine life and the livelihoods, cultures, and lives of communities dependent on them.

Reflections from scientific data for climate advocacy

- Global anthropogenic GHG emissions have risen to the point that the 1.5°C-warming threshold has been breached. National commitments for climate action remain inadequate to mitigate emissions and minimize risks to lives, livelihoods, ecosystems, and other assets.

- While the Asia-Pacific remains a minor contributor to historical emissions driving global climate changes, its current emissions are increasing faster due to rapid economic growth and industrialization. However, its per capita emissions remain much lower than developed nations.

- Compound climate risks, including climate extremes and disasters, are becoming more frequent across the region, with rate of change in temperatures, sea levels, and other climate drivers higher than the global average; these are caused by historical emissions and worsened by current emissions.

- However, despite the occurrences of hazardous climate events, the number of deaths and number of affected people have declined while the number of economically-related assets have suffered significant losses;

Given these findings, the following must inform common advocacy in the spirit of climate justice:

- More ambitious emissions reduction targets must be set in the updated Nationally Determined Contributions, especially of countries with historically high emissions. Additional support must be extended from these countries to LDCs and Developing Countries for the implementation of their NDCs.

- Most countries responsible for historical emissions have not been able to meet their expected contributions, they must help climate-vulnerable nations, including in the Asia-Pacific, to adapt and avert, minimize, and address losses and damages in a timely, just, and equitable manner. Among priority sectors for support include the agricultural and fisheries sectors, aligned with food security, ecosystems protection, and other development goals.

- The NDC commitments of Asia-Pacific countries must also contribute to reductions in current emissions without sacrificing their rights to development, in line with common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.

- Urgent action and support is also needed for addressing the root causes of inequity and inequality within the Asia-Pacific to further enable better climate risk and resilience governance. Attaining these would strengthen food security, protect ecosystems, and reduce poverty.

- Direct financing of community-led actions to address current and future risks must remain at the heart of climate finance.

- We don’t need empty promises [from countries with high historical emissions], we need meaningful climate actions and practices.

[1] World Meteorological Organization. (2025, January 10). WMO confirms 2024 as warmest year on record at about 1.55°C above pre-industrial level [Press release]. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-confirms-2024-warmest-year-record-about-155degc-above-pre-industrial-level

[2] World Meteorological Organization (2025). State of the global climate 2024. https://library.wmo.int/viewer/69075/download?file=State-Climate-2024-Update-COP29_en.pdf&type=pdf&navigator=1

[3] Afifa, Arshad, K., Hussain, N., Ashraf, M., & Saleem, M. (2024). Air pollution and climate change as grand challenges to sustainability. Science of the Total Environment, 928, 172370, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172370

[4] Ritchie, H. (2023). Global inequalities in CO2 emissions. https://ourworldindata.org/inequality-co2

[5] United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) & United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2024). 2024 Review of Climate Ambition in Asia and the Pacific: From Ambitions to Results: Sectoral Solutions and Integrated Action. https://repository.unescap.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/cccf1973-0ad5-4055-9d3b-8fcacecb3aaf/content

[6] World Meteorological Organization. (2024, March 5). El Niño weakens but impacts continue [Press release]. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/el-nino-weakens-impacts-continue

[7] World Weather Attribution (2024, May 14). Climate change made the deadly heatwaves that hit millions of highly vulnerable people across Asia more frequent and extreme. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-made-the-deadly-heatwaves-that-hit-millions-of-highly-vulnerable-people-across-asia-more-frequent-and-extreme/

[8] HeatWatch (2024). Struck by heat: A news analysis of heatstroke deaths in India in 2024. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fEi5Unl9bD_zBxJHf_I9Pm4nziTGIBxD/view

[9] Save the Children (2024, April 25). Bangladesh: Extreme heat closes all schools and forces 33 million children out of school [Press release]. https://www.savethechildren.net/news/bangladesh-extreme-heat-closes-all-schools-and-forces-33-million-children-out-classrooms

[10] Binh, A. (2024, April 14). Drought, salt intrusion destroy Mekong Delta paddy fields. VnExpress International. https://e.vnexpress.net/photo/environment/drought-salt-intrusion-destroy-mekong-delta-paddy-fields-4733890.html#:~:text=The%20rice%20is%20supposed%20to,the%20amount%20of%20damaged%20rice.

[11] Center for Disaster Philanthropy (2025). 2024 Southeast Asia floods. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2024-southeast-asia-floods/

[12] International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2024). Nepal flood and landslide response 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/nepal-flood-and-landslide-response-2024-dref-operation-mdrnp018

[13] Lacuata, R. C. (2024, November 14). From Kristine to Pepito: 6 cyclones batter PH one after another. ABS-CBN News. https://www.abs-cbn.com/news/2024/11/14/from-kristine-to-pepito-6-cyclones-batter-ph-one-after-another-2209

[14] World Weather Attribution (2024, December 12). Climate change supercharged late typhoon season in the Philippines, highlighting the need for resilience to consecutive events. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-supercharged-late-typhoon-season-in-the-philippines-highlighting-the-need-for-resilience-to-consecutive-events/

[15] Shaw, R., Y. Luo, T.S. Cheong, S. Abdul Halim, S. Chaturvedi, M. Hashizume, G.E. Insarov, Y. Ishikawa, M. Jafari, A. Kitoh, J. Pulhin, C. Singh, K. Vasant, and Z. Zhang, 2022: Asia. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1457–1579, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.012.

c/o Rice Watch Action Network

c/o Rice Watch Action Network